In response to the following linked article:

The rebuttal to my article tries to swat away questions of New Testament authorship with some familiar apologetic flourishes: Satan made you doubt, Plato had fewer manuscripts, and Peter could totally spell. Let’s sort through this — with both humor and actual scholarship.

- “Satan made you doubt.”

Apparently the devil isn’t busy enough with wars, greed, and injustice — he’s moonlighting as a textual critic in a dusty library, whispering, “Pssst… Mark 16:9–20 wasn’t original.”

But Christians noticed textual variants long before Bart Ehrman. Origen (3rd century) admitted, “The differences among the manuscripts have become great” (Commentary on Matthew 15.14). Jerome complained about “various readings” in the Latin Bible. Even Augustine admitted some texts circulated “with additions” (On Christian Doctrine 2.12).

So if doubt comes from Satan, then apparently Origen, Jerome, and Augustine were on Beelzebub’s payroll too.

- “But Plato, Aristotle, Homer!”

Yes, Plato has 7 manuscripts, Aristotle 49, Homer 643. The New Testament boasts over 5,000 Greek manuscripts. But as NT scholar Craig Blomberg (an evangelical) admits, “The abundance of manuscripts does not mean we have no variants. Quite the contrary — it means we have hundreds of thousands” (The Historical Reliability of the New Testament, 2016).

Quantity of manuscripts is evidence of popularity, not necessarily authorship. Nobody’s eternal destiny hangs on whether Homer actually wrote the Iliad.

- “We know who wrote the Gospels — their names are in Acts!”

That’s like saying, “Of course J.K. Rowling wrote Shakespeare; her name shows up in a library record.” The Gospels are anonymous. The earliest copies don’t say “The Gospel According to Matthew.” The titles appear in the late 2nd century.

As Raymond Brown (a Catholic scholar) put it bluntly: “The present titles, which ascribe the Gospel to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are not part of the original works but were added later” (Introduction to the New Testament, 1997).

Acts mentioning “Matthew the tax collector” proves only that someone named Matthew was a tax collector — not that he wrote a 28-chapter Greek Gospel.

- “Paul wrote them all. Different style? Just handwriting mood swings.”

The “multi-individuality of handwriting” defense is creative, but irrelevant. Scholars don’t base authorship on penmanship alone. They examine vocabulary, theology, and historical setting.

For instance, Romans and Galatians pulse with Paul’s urgency. Ephesians and Colossians present a cosmic Christology and more structured Greek. That’s why most critical scholars (and even some evangelicals) classify them as “Deutero-Pauline.” Luke Timothy Johnson notes: “The differences in vocabulary, style, and theology are too great to ignore” (The Writings of the New Testament, 2010).

That doesn’t make them fraudulent; pseudonymous writing was common in antiquity. It simply means the Pauline “school” carried forward his theology.

- “The Fathers quoted Paul, so that settles it.”

Yes, Clement, Ignatius, and Polycarp cite letters attributed to Paul. But citing a text shows its authority, not its authorship. Eusebius himself (4th century) admitted debates about certain letters (Ecclesiastical History 3.25).

Patristic testimony proves that by 100–150 CE, churches revered certain letters. It doesn’t prove Paul’s hand wrote each one.

- “Peter could spell. Show me a verse that says he couldn’t!”

This is theological Uno: reverse card. The burden of proof isn’t on me to show Peter couldn’t spell. Acts 4:13 literally calls Peter and John agrammatoi (“uneducated”). That raises a fair question: how likely is it they wrote polished Greek treatises?

Even conservative scholar Ben Witherington admits: “1 Peter’s Greek is too sophisticated for a Galilean fisherman… The hand of a secretary is almost certainly involved” (Letters and Homilies for Hellenized Christians, 2006).

So sure, Peter could “spell” — with help. Inspiration doesn’t mean every apostle suddenly got Rosetta Stone.

- “But John’s Gospel and Revelation sound alike!”

Actually, they don’t. The Gospel of John has elegant Greek; Revelation reads like someone who struggled with grammar. That’s why Dionysius of Alexandria (3rd century) argued they had different authors (Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. 7.25).

Modern scholarship agrees. Craig Koester notes: “The differences in style and vocabulary are stark” (Revelation, Anchor Bible, 2014).

If they’re the same author, then he went from writing like a philosopher to writing like Yoda.

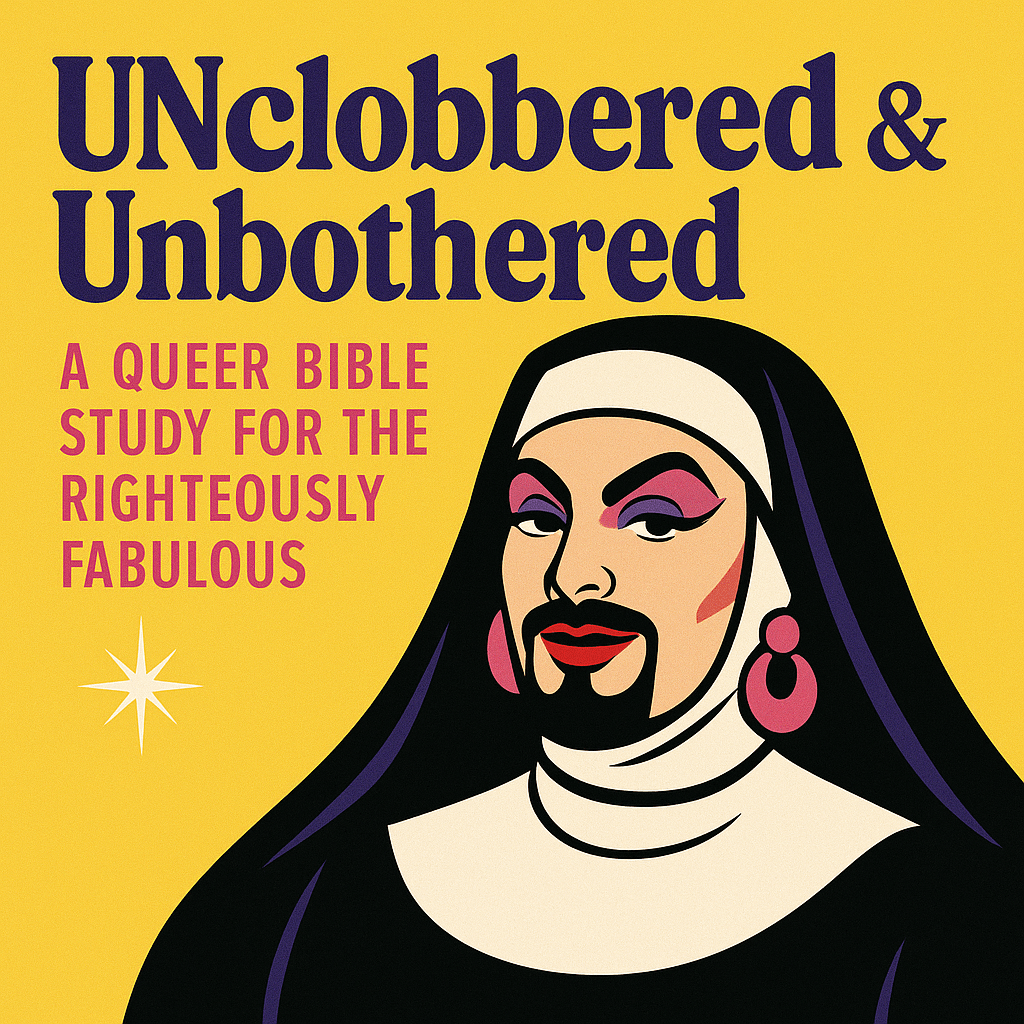

- “You’re transgender, so you can’t be Christian.”

This isn’t scholarship; it’s a playground taunt. My gender identity has nothing to do with whether Mark 16’s “long ending” was original. Attacking the critic instead of engaging the evidence is the definition of ad hominem.

Conclusion: Faith, Facts, and Fear

The New Testament is sacred, beloved, and central to Christian life. But pretending it dropped from heaven leather-bound in King James English doesn’t honor it — it cheapens it.

Admitting that the Gospels are anonymous, that some Pauline letters are disputed, and that later scribes added a few passages doesn’t mean Christianity is false. It means the Bible has a history, just like every other ancient text.

God’s Word isn’t fragile. If faith shatters the moment we admit Mark’s long ending was tacked on later, maybe the problem isn’t the manuscript tradition — maybe it’s our fear of facing the very human story of how God’s Word came to us.